Complications of High PTH in Kidney Disease – 3 Types of Parathyroid Disorders, Treatment Considerations, and Risks.

What Does the Parathyroid Gland Do?

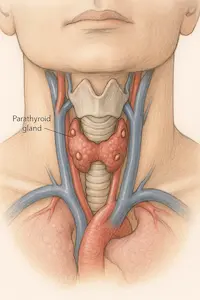

You’ve probably heard of your thyroid—but did you know there’s something called the parathyroid too? There are usually four parathyroid glands located in the thyroid bed. Even though these tissues are neighbors, they have very little dependance on each other. In fact, it is the kidneys which primarily regulate parathyroid function.

These are four tiny glands in your neck that help control how your body uses calcium and phosphorus. They do that by making a hormone called PTH, or parathyroid hormone.

PTH helps keep your bones strong and your blood calcium at the right level. When calcium drops too low, your parathyroid glands release more PTH to bring it back up.

But when there’s high PTH in kidney disease, it’s not because your body is low on calcium—it’s usually because your kidneys aren’t helping regulate things the way they used to. In fact, high PTH in kidney disease is one of the earliest signs that bone and mineral balance is shifting.

Types of Hyperparathyroidism – What’s the Difference?

Not all high PTH means the same thing. There are actually three main types of hyperparathyroidism, depending on what’s causing the problem.

- Primary hyperparathyroidism happens when one or more of the parathyroid glands become overactive on their own. This raises both PTH and calcium, and often leads to kidney stones or bone loss.

- Secondary hyperparathyroidism is common in people with chronic kidney disease. In this case, high PTH in kidney disease happens because the kidneys can’t help balance calcium, phosphorus, or vitamin D properly.

- Tertiary hyperparathyroidism develops after years of secondary hyperparathyroidism. The parathyroid glands become so overactive that they no longer respond to feedback from the body—and may require surgery.

Understanding what type you have helps guide treatment. Most patients with high PTH in kidney disease have secondary hyperparathyroidism, especially in the earlier stages of CKD.

The Vitamin D Connection – Why Kidney Function Matters

To understand why there’s high PTH in kidney disease, we have to talk about vitamin D—and how your body activates it.

Vitamin D from food or supplements isn’t fully active yet. It has to go through two steps before your body can use it:

- First, your skin activates it when you get sunlight.

- Then, your kidneys finish the job, turning it into the form that regulates calcium and tells your parathyroid glands to slow down.

When your kidneys aren’t working well, that second step doesn’t happen. The parathyroid glands don’t get the message to relax, so they keep pumping out more and more PTH.

That’s why high PTH in kidney disease is often caused by a lack of active vitamin D, even if you’re taking supplements. Without enough active vitamin D, your body can’t properly control calcium or suppress PTH.

Why Isn’t My PTH Supposed to Be “Normal”?

This is a common—and very reasonable—question. You get lab work back, and your PTH level is flagged as “high.” But then your kidney doctor tells you not to worry about getting it into the “normal” range. What gives?

In people with healthy kidneys, we aim to keep PTH within a narrow, standard range. But when someone has chronic kidney disease, we actually adjust the goalposts.

Here’s why:

- Trying to force PTH into a normal range can actually be harmful.

- In kidney disease, some elevation is expected—and even necessary—to maintain healthy bones.

- The target range for PTH gets higher as kidney function declines.

For example:

- In early CKD, we aim for PTH to stay between the upper limit of normal and twice that level, especially if your calcium is low.

- In people on dialysis, we often accept PTH levels between 150 and 600, depending on your labs and symptoms.

That’s because over-suppressing PTH can lead to adynamic bone disease—a condition where your bones stop remodeling and become weak, brittle, and prone to fracture.

So while it may feel strange to let your PTH stay elevated, it’s part of protecting your bones in the long run. That’s why managing high PTH in kidney disease looks different than in people without CKD.

How High PTH Affects the Body

When PTH levels remain elevated, your body begins to feel the consequences—sometimes gradually, sometimes suddenly. High PTH in kidney disease leads to a constant signal for your bones to release calcium into the blood, but this disrupts more than just your skeleton.

Common effects of long-standing high PTH in kidney disease include:

- Bone pain and increased fracture risk from excessive bone turnover

- Fatigue, muscle weakness, or restless legs, especially in dialysis patients

- Calcium deposits in blood vessels, leading to stiff arteries and high blood pressure

- Poor wound healing due to impaired circulation and tissue damage

- Calciphylaxis—a rare but serious condition where calcium builds up in small blood vessels of the skin and fat, causing painful ulcers that are difficult to treat

Calciphylaxis is more common in people with very high PTH in kidney disease, especially when phosphorus is also elevated. It is a medical emergency requiring urgent care. It can result in loss of limb and increased mortality risk in general.

The longer PTH stays high, the more likely these complications become. That’s why your nephrologist watches trends over time and balances treatment to avoid both extremes—too high and too low.

The Role of Phosphorus – Why Controlling It Matters

Even though this article focuses on PTH, we can’t ignore phosphorus—because it plays a huge role in whether or not PTH stays in check.

In kidney disease, phosphorus builds up in the blood because the kidneys can’t get rid of it well. This triggers the parathyroid glands to make more PTH—one of the earliest causes of high PTH in kidney disease.

If phosphorus stays high:

- It becomes very difficult to bring PTH down.

- It speeds up bone loss and vascular calcification.

- It contributes to the development of tertiary hyperparathyroidism, where the glands no longer respond to normal signals and may require surgery.

That’s why your care team might recommend:

- Low-phosphorus diets

- Phosphate binders with meals

- Label reading to avoid hidden phosphorus additives

Even if you’re doing everything else right, high phosphorus can block success in managing high PTH in kidney disease.

For a full breakdown of phosphorus and dietary considerations, see our What You Need to Know About Phosphorus rack card.

How Is High PTH Treated? Understanding Your Options

When diet and phosphorus control aren’t enough to manage high PTH in kidney disease, your doctor may recommend medications to help bring it down safely.

There are two main types of medicines used to treat secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism:

1. Active Vitamin D Analogs

These medications help your body absorb calcium and send a signal to your parathyroid glands to slow down. They mimic the fully activated form of vitamin D that the kidney normally makes—but in CKD, your body can’t produce it on its own.

Examples include:

- Calcitriol

- Paricalcitol

- Doxercalciferol

These are often taken orally or given during dialysis. Your doctor will choose the one that best fits your lab profile, especially your calcium and phosphorus levels.

2. Calcimimetics

Calcimimetics like cinacalcet work differently. They make the parathyroid gland more sensitive to calcium, helping lower PTH without raising calcium or phosphorus levels. These are especially useful if your calcium is already high and vitamin D analogs can’t be used safely.

What If It’s Not Clear Which Treatment to Use?

In some cases, your PTH levels and symptoms don’t match up. That’s when your doctor might look at another lab called bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BS-ALP).

- BS-ALP is a marker of bone turnover—how fast your bones are breaking down and rebuilding.

- A high BS-ALP suggests your bones are turning over too quickly (which may support more treatment).

- A low BS-ALP, especially if PTH is also low, could mean your bones are underactive—a condition called adynamic bone disease, where aggressive PTH treatment could actually do harm.

Using BS-ALP can help your doctor make smarter, safer decisions about how to treat high PTH in kidney disease, especially in complex or borderline cases.

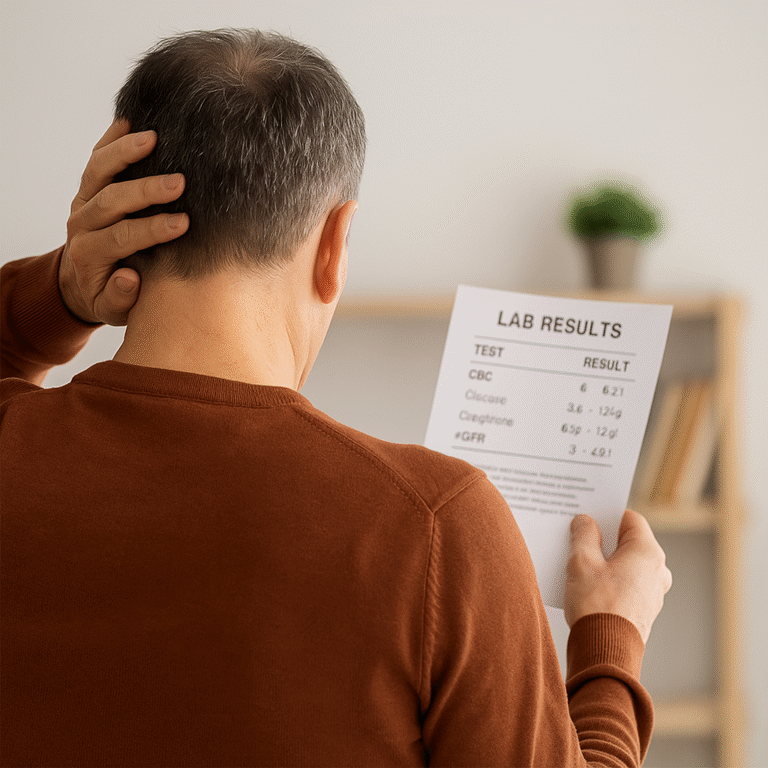

What Can You Do as a Patient?

Managing PTH isn’t only about medication. You can play a major role in keeping things on track—especially when it comes to diet, labs, and follow-up.

Ways to support your care:

- Learn your lab targets based on your stage of kidney disease

- Follow your phosphate restriction plan and ask for help from your dietitian

- Take vitamin D or phosphate binders exactly as prescribed—especially with meals

- Keep a copy of your lab results and bring questions to your appointments

- Avoid skipping labs or check-ins, even when you’re feeling well

Understanding what PTH does—and why your targets may be different—is one of the best ways to stay ahead of high PTH in kidney disease.

Final Thoughts

It’s normal to feel confused or overwhelmed when you first hear that your parathyroid hormone is high. But high PTH in kidney disease is something we expect—and can manage—when we understand the causes and act early.

Your kidneys play a key role in keeping PTH balanced. When they stop activating vitamin D or clearing phosphorus, the parathyroid glands respond. The goal isn’t to force PTH into the normal range—it’s to keep your bones active but safe, your vessels clear, and your body in balance.

We’ll explore phosphorus, diet, and binder strategies in more detail in our upcoming guide. For now, know that you have options, and your care team is here to help you navigate them.

Works Cited

- KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of CKD–MBD. Kidney Int Suppl. 2017;7(1):1–59.

- Sprague SM. “Understanding PTH Targets in Dialysis.” CJASN. 2008;3(2):S38–S43.

- Gal-Moscovici A, Sprague SM. “Use of Bone Turnover Markers in Chronic Kidney Disease.” Kidney Int. 2007;71(1):12–19.

- National Kidney Foundation. What is Hyperparathyroidism? Accessed July 2025