Contrast Risk in CKD: A Shifting Paradigm

Understanding Contrast Risk in CKD

For decades, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) were routinely considered at high risk for complications from intravenous contrast agents used in imaging studies. This concern primarily focused on contrast-associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) and, in specific scenarios, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) related to gadolinium exposure. Contrast risk in CKD became almost synonymous with caution, delay, and sometimes outright avoidance of contrast-enhanced imaging.

The basis for this caution was not unfounded. Early observational studies suggested that contrast administration could precipitate abrupt declines in kidney function, particularly in patients with reduced baseline glomerular filtration rate (GFR), diabetes, or concurrent nephrotoxin exposure. Over time, however, methodological limitations of these studies—such as inadequate control groups and failure to account for confounding risk factors—have been recognized.

As a result, the contemporary conversation around contrast risk in CKD is evolving. Instead of relying on blanket restrictions, clinicians are now urged to weigh the diagnostic value of contrast studies against individualized patient risk, using refined evidence and updated guidelines.

Evolution of the Risk Paradigm

The older paradigm treated CKD as a near-absolute contraindication to many contrast-enhanced procedures. Patients were often diverted to non-contrast alternatives, which could compromise diagnostic accuracy and delay care. The pendulum began to swing on contrast risk in CKD when large-scale, propensity-matched studies challenged the causality between contrast exposure and acute kidney injury in many patient populations.

For iodinated contrast, data from emergency department and inpatient settings indicated that when matched against non-contrast controls, the rates of AKI were similar. This does not mean risk is absent—particularly in patients with advanced CKD, unstable hemodynamics, or multiple insults to kidney function—but it does mean that contrast risk in CKD may have been overestimated in the past.

In the realm of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs), similar reassessment occurred. The link between certain linear gadolinium agents and NSF is now well-established, but the introduction of macrocyclic GBCAs with more stable chelation chemistry has markedly reduced this risk. This evidence supports a more individualized evaluation of contrast risk in CKD rather than an automatic deferral of enhanced imaging.

Iodinated Contrast and Acute Kidney Injury

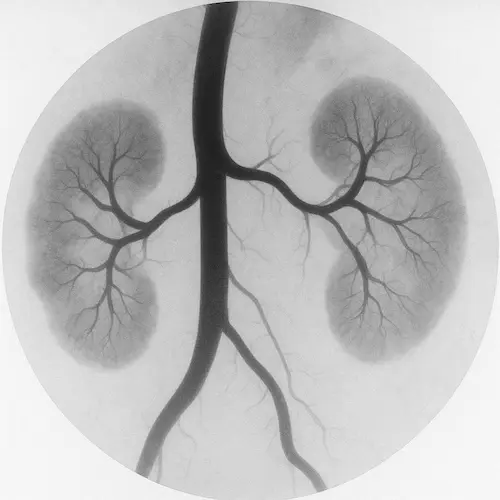

Iodinated contrast media are indispensable in CT angiography, CT urography, and many interventional radiology procedures. Historically, “contrast-induced nephropathy” (CIN) was the term used to describe an acute rise in serum creatinine after exposure. Today, that terminology has shifted toward “contrast-associated acute kidney injury” (CA-AKI), reflecting the recognition that not all kidney injury temporally related to contrast exposure is caused by the contrast itself.

Modern studies, particularly those employing matched control groups, have shown that in many cases—especially when baseline estimated GFR (eGFR) is above 30 mL/min/1.73 m²—the incidence of true contrast-induced injury is far lower than once feared. However, risk is not eliminated. Patients with advanced CKD, active volume depletion, concurrent nephrotoxins, or hemodynamic instability remain more vulnerable. In these individuals, contrast risk in CKD still carries meaningful clinical weight.

When iodinated contrast is necessary in higher-risk patients, strategies such as isotonic volume expansion before and after the procedure, minimizing contrast dose, and avoiding unnecessary repeat exposures can help mitigate harm. Understanding contrast risk in CKD also ensures that preventive measures are applied without unnecessary delay to critical imaging.

Gadolinium-Based Contrast and Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis

The early 2000s brought intense concern over nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a debilitating and potentially fatal fibrosing disorder of the skin and internal organs linked to certain gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs). Risk was greatest in patients with advanced CKD (especially those on dialysis) and in those receiving high or repeated doses of less stable linear gadolinium agents. This was a different type of contrast risk in CKD as the organs at risk were not necessarily the kidneys.

Since then, the field has shifted dramatically. Macrocyclic GBCAs—designed with more stable chelation of gadolinium—demonstrate a far lower association with NSF, even in advanced CKD. Current evidence suggests that when these agents are used judiciously, the risk is exceedingly small, though caution and informed consent remain essential.

Patients with eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m² should still undergo careful benefit–risk assessment before GBCA exposure, and dialysis-dependent patients should ideally receive post-procedure hemodialysis to facilitate gadolinium clearance. Yet, as with iodinated contrast, the modern understanding of contrast risk in CKD now supports a more balanced, evidence-based approach rather than absolute avoidance.

Updated KDIGO Guidance: What’s Changed and What to Do in Practice

The most recent KDIGO guidelines on acute kidney injury and CKD management reflect the evolving evidence base. Key updates regarding contrast exposure include:

- Risk Assessment Over Blanket Prohibition: KDIGO now emphasizes individualized risk stratification using factors such as eGFR, volume status, concurrent medications, and urgency of diagnostic imaging.

- Preferred Preventive Strategy: For at-risk patients, isotonic intravenous fluids—typically normal saline—remain the cornerstone of prevention, with oral hydration as an adjunct where feasible.

- Pharmacologic Prophylaxis: Agents like N-acetylcysteine, once widely used, are no longer recommended given lack of consistent benefit.

- Gadolinium Selection: When MRI contrast is required in CKD, macrocyclic agents are preferred over linear agents due to their lower propensity for gadolinium release and NSF risk.

- Avoidance of Delay: In urgent scenarios, delaying necessary imaging to await kidney function testing should be avoided if it jeopardizes patient outcomes.

Incorporating KDIGO’s updated position into daily practice helps ensure that contrast risk in CKD is approached as a modifiable concern rather than an absolute barrier to diagnostic imaging.

Patient Selection and Risk Stratification

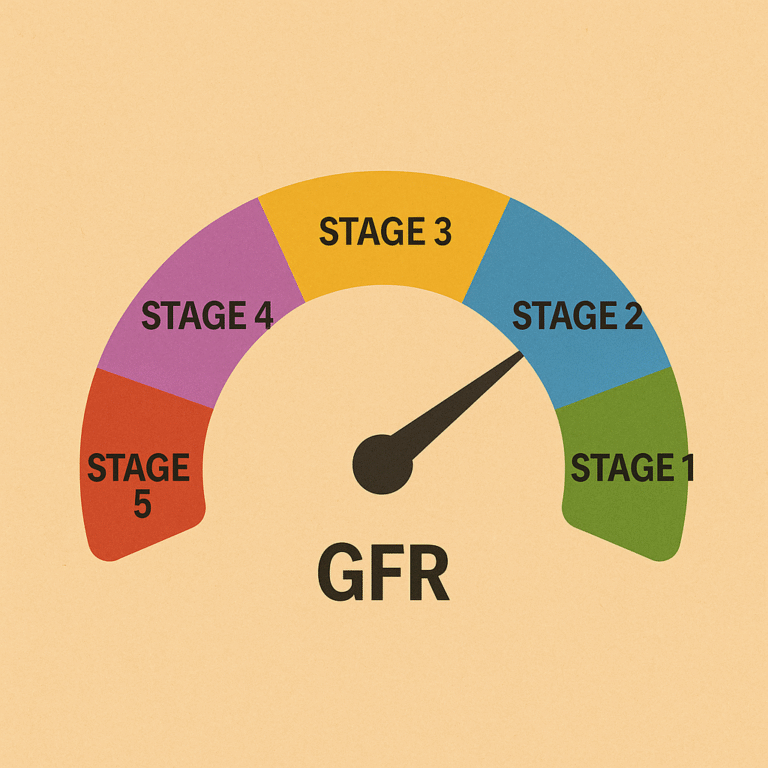

Not every patient with CKD carries the same vulnerability to contrast-related harm. The most informative risk assessments combine laboratory data with the clinical context. For example, a patient with stage 3a CKD who is hemodynamically stable, well-hydrated, and not taking nephrotoxic drugs has a very different outlook than a patient with stage 4 CKD, active sepsis, and concurrent NSAID use.

Risk stratification tools—such as the Mehran score for coronary angiography—can help quantify likelihood of AKI, though most are procedure-specific. Regardless of the tool used, the principle remains the same: integrate kidney function, comorbidities, and procedural urgency into decision-making. This approach aligns with KDIGO’s shift from rigid exclusion criteria toward individualized, context-sensitive evaluation of contrast risk in CKD.

Modern Prevention Strategies

Prevention starts before the procedure. For at-risk patients, isotonic intravenous hydration—typically with normal saline at a rate of 1–3 mL/kg/hour before and after the study—is the most consistently effective measure. Oral hydration can supplement IV fluids when logistics or patient preference dictate, but should not replace them in high-risk scenarios.

Contrast dosing should be minimized without sacrificing diagnostic yield. This often involves using the lowest volume of contrast that will still produce adequate opacification, aided by modern low-osmolar or iso-osmolar contrast agents. Avoiding repeated contrast studies in a short time frame also reduces cumulative risk. Understanding contrast risk in CKD in the context of prevention helps reinforce why dose reduction and agent selection matter.

For gadolinium, the strategy hinges on agent selection: macrocyclic GBCAs at the lowest necessary dose, with post-procedure dialysis for those already on renal replacement therapy. Importantly, prophylactic medications such as N-acetylcysteine or high-dose statins—once popular—are no longer recommended in routine practice due to lack of proven benefit in preventing CA-AKI.

Balancing Diagnostic Benefit Against Risk

The decision to use contrast in a patient with CKD is rarely black-and-white. The benefits of enhanced imaging may include early cancer detection, accurate vascular mapping before surgery, or rapid diagnosis of life-threatening conditions. In these cases, the value of the diagnostic information can far outweigh the relatively modest and manageable risks of CA-AKI or NSF.

The modern paradigm encourages clinicians to frame the conversation around shared decision-making. Patients should understand not only the potential kidney-related risks, but also the risks of forgoing contrast-enhanced imaging—such as missed diagnoses, delayed treatment, or the need for more invasive tests. This balanced perspective ensures that contrast risk in CKD is seen within the broader context of overall patient outcomes.

Takeaway

The concept of contrast risk in CKD is undergoing a profound transformation. While vigilance remains critical—especially in advanced CKD or unstable patients—current evidence supports a more nuanced, individualized approach. Updated KDIGO guidelines reinforce this shift, urging clinicians to focus on risk stratification, preventive hydration, and appropriate agent selection rather than reflexive avoidance.

In practice, this means that contrast-enhanced imaging should not be dismissed out of hand for CKD patients. Instead, it should be approached thoughtfully, with preventive strategies in place and a clear understanding of the diagnostic benefits at stake. This evolving balance between caution and clinical necessity reflects a more mature, evidence-informed approach to kidney care in the imaging era.

References

ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. “ACR Manual on Contrast Media.” American College of Radiology; 2024.

Davenport MS, et al. “Contrast material–induced nephrotoxicity and intravenous low-osmolality iodinated contrast material.” Radiology. 2013;267(1):94–105. Link

KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2021;11(4):1–115.