Is CKD Reversible? Breaking Down Acute vs Chronic

A Fair Question With a Nuanced Answer

One of the most common and understandable questions we hear after someone is diagnosed with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is ” Can CKD be reversible?”

And the honest answer is:

It depends.

CKD is a spectrum — not a single disease — and the potential to reverse or recover kidney function depends on what caused it, how early it’s caught, and how your body responds to care. Let’s unpack what “reversibility” really means in kidney terms.

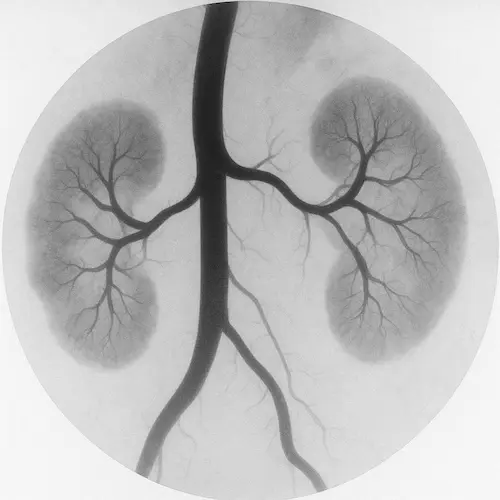

CKD vs. AKI: Chronic vs. Acute

First, it’s important to distinguish between Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) and Acute Kidney Injury (AKI):

- CKD is a long-term, often gradual decline in kidney function that persists over time. It’s typically not fully reversible, but it can often be slowed or stabilized.

- AKI is a sudden drop in kidney function that happens over hours to days, often due to dehydration, infection, medication effects, or obstruction. AKI is often reversible, especially when caught early.

Sometimes, CKD and AKI occur together. For example, someone with Stage 3 CKD who becomes dehydrated and takes ibuprofen might experience an AKI on top of their existing CKD. If that AKI is reversed, kidney function may return to its prior baseline — but not higher. This is not always the case, however, because AKI is not always reversible. Chronically damaged kidneys can have a difficult time bouncing back from additional injury.

Causes That May Be Reversible (or Partially Reversible)

Certain underlying causes of kidney damage can be treated or corrected, especially if identified early. These include:

- Obstruction (like kidney stones or enlarged prostate): If urine flow is restored, kidney function can improve.

- Dehydration or low blood volume: Fluids can help return kidneys to baseline.

- Certain autoimmune conditions (like lupus nephritis): With medication, inflammation can be reduced, preventing further damage.

- Medication toxicity (e.g., NSAIDs, some antibiotics, contrast dyes): Stopping the offending drug may allow for partial recovery.

- High blood pressure and diabetes: These can’t be “cured,” but better control can stop or slow CKD progression — and sometimes even lead to small improvements in eGFR.

However, once significant scarring (fibrosis) occurs in the kidneys, that damage is generally not reversible. Think of it like a scar on your skin — the function is lost where tissue has hardened.

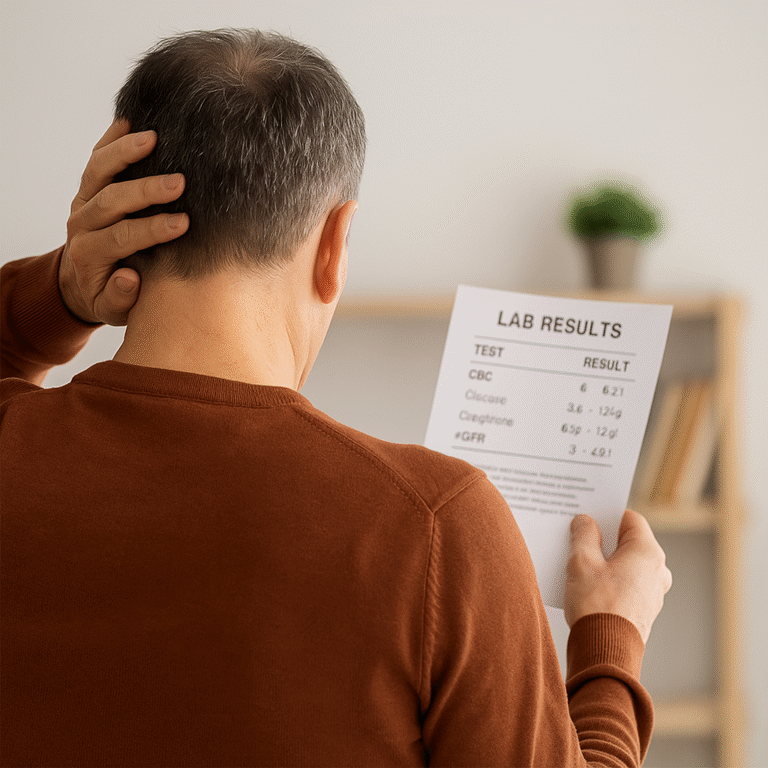

What “Stabilization” Really Means

Even if your kidney function doesn’t improve numerically, holding steady is a win. Many people with CKD remain in the same stage for years — even decades — without needing dialysis. That’s thanks to:

- Blood pressure and glucose control

- Avoidance of further kidney insults

- Dietary modifications

- Adjusted medications

- Close monitoring by your care team

If your labs are consistent, symptoms are minimal, and you’re not progressing — that’s a success.

False Hope vs. Real Progress

We caution patients against miracle supplements or “kidney detox” fads that promise full reversal. These are often not supported by evidence, and some can actually be harmful. Instead, we encourage a science-backed approach that includes:

- Consistent follow-up

- Shared decision-making with your provider

- Addressing reversible factors early

- Lifestyle adjustments that support overall kidney health

There’s no quick fix, but there is a path forward — and in many cases, room for optimism.

The Takeaway

Not all kidney damage is permanent — especially when caused by short-term or reversible triggers. But in chronic cases, the focus shifts from “Can I go back to normal?” to “How can I stay where I am — or slow down the clock?”

Ask your provider about the cause of your CKD and whether any part of it might be reversed or improved. It’s a conversation worth having. A deep-dive into AKI can be found at the widely regarded KDIGO archive

References

- Kellum JA, Lameire N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary. Crit Care. 2013;17(1):204.

- Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165–180.