Improve Your Diet: The Impact of Nutritional Focus on Preserving Kidney Health

The Fork as a Tool for Kidney Health

When you’re living with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the choices you make in the kitchen matter almost as much as the ones you make in the clinic. Food isn’t just fuel — it can act as medicine, a source of stress, or a safeguard, depending on how it’s chosen and prepared.

But what exactly does “kidney-friendly” mean?

That phrase often gets tossed around in vague or contradictory ways, especially online. The truth is, there’s no one-size-fits-all renal diet. Nutrition for CKD depends on many variables — your disease stage, recent lab values, comorbidities like diabetes or hypertension, and whether or not you’re on dialysis. What’s helpful for one person may be risky for another.

Still, some guiding principles apply across the board. These principles aren’t meant to be rigid rules, but rather tools — flexible and powerful, when wielded with intention. Let’s unpack the why behind common dietary recommendations for CKD and walk through simple, evidence-backed choices you can make every day.

Why Diet Matters in CKD

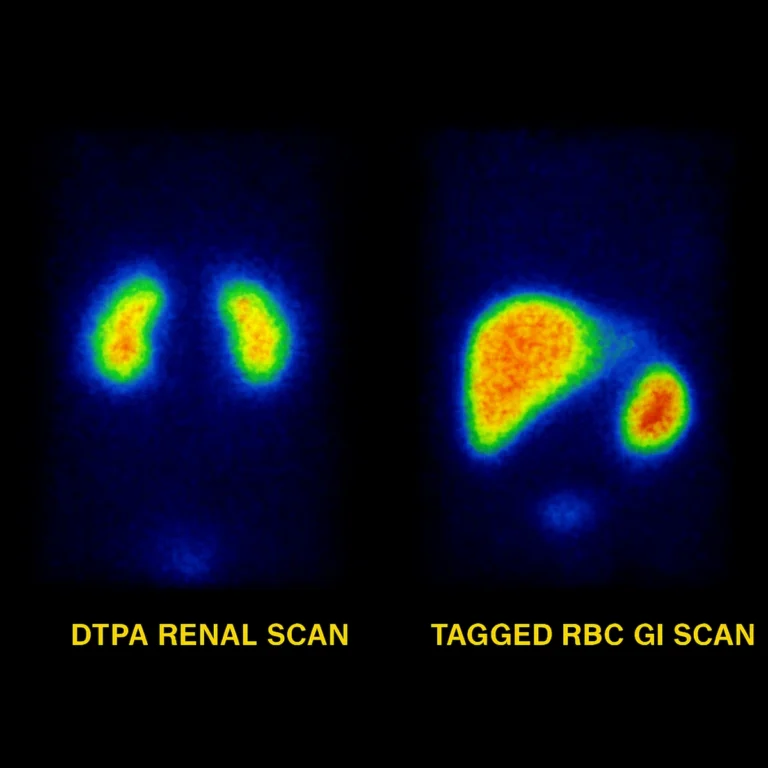

Your kidneys are incredible multitaskers. Under normal conditions, they help filter out excess sodium, potassium, phosphorus, acid, and water. They regulate the metabolism of protein, balance electrolytes, activate vitamin D, and even contribute to hormone production for red blood cell formation and blood pressure control.

But when kidney function declines, these processes begin to falter. Waste and fluid build up. Electrolyte imbalances become more likely. And the body’s ability to buffer acid or metabolize protein shifts, often silently at first.

That’s where nutrition becomes not just supportive, but essential. A targeted approach to diet can:

- Prevent dangerous electrolyte buildup

- Reduce toxic byproducts from protein metabolism

- Ease blood pressure and fluid retention

- Lower systemic inflammation and oxidative stress

- Slow the progression of kidney damage

Importantly, these effects don’t require radical overhauls. Even small dietary shifts — fewer packaged foods, more label reading, cooking with intention — can influence your labs and how you feel over time.

If you need help building a balanced, kidney-safe plate, our CKD-DASH diet card breaks it down with easy portion tips and food group suggestions you can use right away.

Sodium: Enemy of Fluid Balance

Sodium plays a central role in how the body retains fluid. When intake exceeds what the kidneys can excrete, the result is water retention — swelling, increased blood pressure, and strain on the heart. This excess fluid can also reduce the effectiveness of medications, particularly antihypertensives.

That’s why most people with CKD are advised to limit sodium to less than 2,300 mg per day. For some, especially in later stages or with fluid overload, the target may be closer to 1,500–2,000 mg.

Why it matters:

- High sodium leads to volume expansion — worsening blood pressure and edema.

- It can contribute to left ventricular hypertrophy and long-term cardiovascular damage.

- It increases proteinuria, which is itself a driver of CKD progression.

Watch out for hidden sodium in:

- Canned soups and vegetables

- Frozen entrees and boxed meal kits

- Deli meats, bacon, and seasoned chicken

- Restaurant food and fast food (even “healthy” options)

- Shelf-stable snacks like crackers, granola bars, and dressings

Instead, reach for:

- Fresh or frozen vegetables without added sauce

- Herbs, citrus, garlic, and vinegar to flavor meals

- Homemade dressings, low-sodium broths, and no-salt-added canned goods

Learning to season without salt is one of the most empowering tools you can bring into your kitchen. It’s not about bland food — it’s about flavor built on depth, not default.

Protein: The Balance Is the Point

Protein has become a complicated subject in CKD nutrition — and rightly so. While it’s essential for maintaining muscle, immune function, and overall health, too much protein can increase nitrogenous waste (like urea), acid load, and phosphorus — all of which the kidneys must handle.

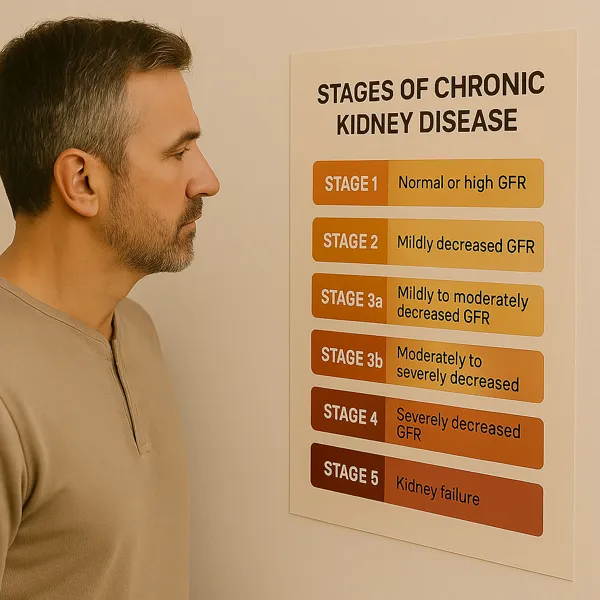

In early CKD (Stages 1–2), protein intake often doesn’t need to be restricted. But as kidney function declines, especially in Stages 3–5 (not yet on dialysis), moderate protein restriction is often recommended: around 0.6–0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day.

That doesn’t mean eliminating protein — it means shifting toward quality and moderation.

Choose:

- Plant-based sources like beans, lentils, tofu, and quinoa (as potassium allows)

- High-biological-value proteins in small portions — eggs, fish, and lean poultry

Avoid:

- Super-sized meat portions, protein powders, or excess processed meats

Once dialysis starts, the picture changes. Protein needs increase to compensate for losses during treatment, and patients are usually encouraged to eat 1.2–1.4 grams/kg/day.

The key? Your needs change with your labs — and your nutrition plan should too.

Potassium & Phosphorus: Hidden in Healthy Foods

Some of the most nutrient-rich foods — tomatoes, avocados, bananas, nuts — are also high in potassium or phosphorus. These minerals are critical for nerve conduction, muscle function, and bone health — but when kidneys can’t keep up, even good things can become dangerous.

Potassium overload can cause arrhythmias, fatigue, or muscle weakness.

Phosphorus buildup contributes to bone demineralization and soft tissue calcification, including vascular damage.

Watch for:

- Potassium: bananas, oranges, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, spinach, melons

- Phosphorus: colas, processed meats with phosphate additives, nuts, dairy, whole grains

Tips:

- Leach high-potassium vegetables like potatoes and carrots to lower content

- Boil rather than roast or bake certain foods to reduce mineral load

- Check labels for “phos-” additives — these are often absorbed at near 100%

Not everyone with CKD needs to restrict potassium or phosphorus from the start. Let your lab values guide your choices, not fear or internet lists. A renal dietitian can help personalize these decisions without compromising overall nutrition.

Fluids: Not Always a Free-For-All

In early CKD, fluid intake isn’t usually restricted. But that changes as the disease progresses — especially if urine output declines or heart function is affected.

Too much fluid can lead to:

- Swelling (edema)

- Shortness of breath from fluid in the lungs

- High blood pressure and cardiovascular strain

Your doctor may advise tracking your fluid intake or limiting it to a specific amount per day if symptoms or lab markers suggest overload. This includes all fluids — water, coffee, soup, gelatin, and ice.

That said, fluid restriction without cause can backfire, leading to dehydration, low blood pressure, and dizziness. Always check before restricting.

The Bigger Picture: Food as Partnership

Nutrition is not just about lab numbers or restriction — it’s about support, empowerment, and daily decisions that accumulate into something powerful. When you eat well with kidney disease, you’re not just “avoiding problems.” You’re actively building a better foundation for strength, energy, and long-term resilience.

What you can start today:

- Read labels and choose lower-sodium options

- Cook more meals at home to control ingredients

- Favor fresh ingredients over packaged foods

- Talk to your healthcare team before making major changes

If you can access one, a renal dietitian is an invaluable guide — not just for food lists, but for translating labs into personalized strategies you can sustain.

The Takeaway

You don’t have to follow a perfect, restrictive diet to protect your kidneys — but you do need to stay informed, pay attention to your labs, and choose your foods with intention. Nutrition plays a tremendous role not only in slowing CKD progression, but also in helping patients feel better and maintain their health through every stage, including dialysis.

Your kidneys may be working harder — but with the right fuel, you can ease their burden and reclaim a sense of control.

References

- Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fouque D. Nutritional management of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1765–1776.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition for chronic kidney disease. https://www.eatright.org

- National Kidney Foundation. https://www.kidney.org/nutrition