Targeted Therapy for Delaying Progression of CKD: 4 Standouts and More

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) rarely moves in a straight line. Some people experience stable kidney function for years. Others notice a slow, steady decline. And for some, deterioration occurs so rapidly that dialysis or transplant becomes necessary in just a few years. What causes this variation? The answer lies in understanding the progression of CKD.

This progression of CKD is not automatic. Although CKD is a chronic diagnosis, the speed and severity with which it advances differ greatly between individuals. Some of this has to do with conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure. But it also involves less obvious factors—like the amount of protein in the urine, genetic predisposition, and how closely a patient adheres to medical guidance.

Nephrologists evaluate these factors to predict and influence outcomes. Understanding the risks that contribute to progression of CKD enables clinicians to identify treatment opportunities, apply preventive strategies, and tailor treatment to the patient’s individual circumstances. From a patient perspective, knowing what fuels kidney decline can spark proactive decisions about lifestyle, medication, and follow-up care.

In this article, we explore the most influential risk factors for CKD worsening—those that stand out for their impact and those that, while less visible, still contribute meaningfully to the progression of CKD. We’ll also examine how treatment has evolved, and how both science and self-care can alter the path ahead.

Understanding the Progression of CKD

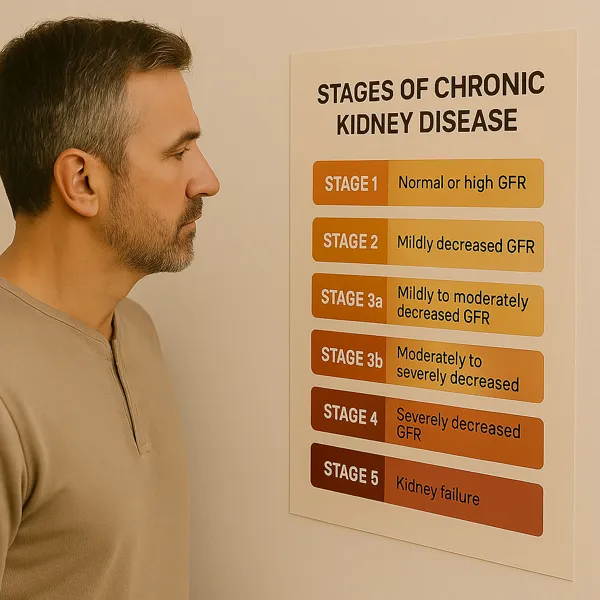

CKD is defined by a sustained reduction in kidney function or evidence of structural kidney damage for over three months. Its severity is staged based on eGFR, a calculation that estimates how effectively the kidneys filter blood. In Stages 1 and 2, eGFR may remain within normal limits, but warning signs such as proteinuria or abnormal imaging signal early disease. Once eGFR dips below 60, the label shifts to Stage 3—indicating moderate kidney function loss.

The progression of CKD refers to the gradual decline in eGFR over time. This rate is not uniform. Most individuals naturally lose only 1–2 mL/min/year, while more than that suggests active progression of CKD Left unchecked, this downward spiral can culminate in end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), requiring dialysis or transplant.

Multiple variables accelerate this descent. Uncontrolled hypertension, poorly managed diabetes, protein leakage in the urine, and recurrent episodes of acute kidney injury all play a role. So do non-modifiable factors like age, race, and family history.

What matters most is that the progression of CKD is rarely linear and never inevitable. With vigilant monitoring, evidence-based therapy, and shared decision-making, this course can often be altered—delayed significantly, and in some cases, even plateaued for years.

Hypertension: The Silent Accelerator

Hypertension is one of the most common and insidious drivers of the progression of CKD. It not only causes kidney disease, but once CKD is present, it hastens decline in a self-reinforcing cycle.

High blood pressure damages the small blood vessels in the kidneys, particularly the glomeruli, the microscopic filters responsible for cleansing the blood. Over time, persistent hypertension stiffens and scars these vessels, decreasing their filtering capacity. As nephron units are lost, the workload shifts to the remaining ones, raising intraglomerular pressure and speeding the progression of CKD.

The danger lies not just in hypertension itself but in its often symptomless nature. Many patients don’t realize their blood pressure is high, or they believe it’s under control when in fact it fluctuates or spikes at times of stress or medication lapses. These cumulative exposures do quiet but lasting damage.

Tight blood pressure control has been consistently shown to slow the progression of CKD, especially in patients with proteinuria. The 2021 KDIGO Blood Pressure Guideline recommends a target systolic pressure under 120 mmHg for most patients with high-risk CKD. Achieving this goal may require multiple medications and sustained lifestyle changes.

Medications that block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)—including ACE inhibitors and ARBs—are especially valuable. They reduce not just blood pressure but also protein leakage, providing a twofold benefit in limiting the progression of CKD. These agents help relax the blood vessels within the kidney and mitigate glomerular hypertension.

But pharmacologic therapy alone is not enough. Lifestyle modifications play a parallel role:

- Sodium restriction is foundational, ideally limiting intake to less than 2,300 mg/day.

- Physical activity, even modest daily walking, improves vascular tone and metabolic health.

- Weight management and limiting alcohol support stable pressure over time.

Importantly, treatment targets must be individualized. For elderly patients or those at risk of falls, overly aggressive blood pressure lowering may cause dizziness or instability. Nephrologists weigh these tradeoffs carefully, adjusting regimens to maximize kidney protection while minimizing harm.

Home blood pressure monitoring, medication adherence, and regular follow-up are vital to success. Patients who engage in their care—tracking numbers, recognizing symptoms, communicating changes—help their clinicians fine-tune treatment. These small acts can greatly affect the progression of CKD over months and years.

In short, hypertension is more than a contributor—it is a central driver of kidney decline. But when managed precisely, it can be transformed from a silent accelerator into a controlled variable in preserving long-term kidney health.

Diabetes and Blood Sugar Control

If hypertension pushes kidney function downhill, diabetes lays the groundwork for the slide. It is the single most common cause of CKD in the United States and a major contributor to the progression of CKD worldwide.

The mechanism is straightforward but relentless: chronically elevated blood sugar damages the microscopic vessels within the kidney, especially the glomerular basement membrane. This leads to diabetic nephropathy, a structural breakdown of the filtration barrier that permits albumin to leak into the urine and distorts glomerular architecture. Over time, these changes impair filtration and accelerate the progression of CKD.

But diabetes doesn’t operate in isolation. It amplifies other threats—hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammation—and often coexists with obesity and cardiovascular disease. Together, these factors form a cluster of metabolic stress that burdens the kidney and hastens functional loss.

The solution starts with glycemic control. Landmark studies like the DCCT and UKPDS demonstrated that lower HbA1c levels reduce microvascular complications, including those affecting the kidney. Most CKD patients benefit from keeping A1c between 6.5% and 7.5%, depending on age, comorbidities, and risk of hypoglycemia.

Yet not all diabetes medications are equal in delaying progression of CKD. Several newer agents have changed the treatment landscape—most notably:

- SGLT2 inhibitors, which reduce blood glucose by promoting urinary excretion. Beyond glycemic control, these agents lower intraglomerular pressure, reduce albuminuria, and slow the progression of CKD regardless of diabetic status.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists, which aid in weight loss, reduce inflammation, and improve insulin sensitivity. They offer additional protection, especially in patients with both CKD and cardiovascular risk.

These therapies are now part of guideline-directed care and are often used alongside traditional agents like metformin (when renal function allows). Close monitoring is essential to ensure safe use and to adjust therapy as kidney function evolves.

Still, medication is only part of the strategy. Diet plays a critical role—particularly carbohydrate quality and portion control. Reducing sugary beverages, processed starches, and excess sodium helps stabilize both glucose and blood pressure. Patient education and access to a renal dietitian can enhance long-term success.

Self-monitoring of glucose, medication adherence, and regular lab checks allow early detection of trends and complications. Engaged patients are more likely to recognize warning signs, avoid nephrotoxic agents, and work collaboratively with their providers.

Diabetes poses a significant threat to kidney health, but it is also one of the most modifiable factors influencing the progression of CKD. With the right tools, timing, and team, many patients can slow or even halt its impact.

Proteinuria and the Role of Albuminuria

Protein in the urine—especially albumin—is one of the most powerful predictors of the progression of CKD. More than a passive marker, proteinuria is an active contributor to kidney damage, driving inflammation and scarring in the tubulointerstitial space.

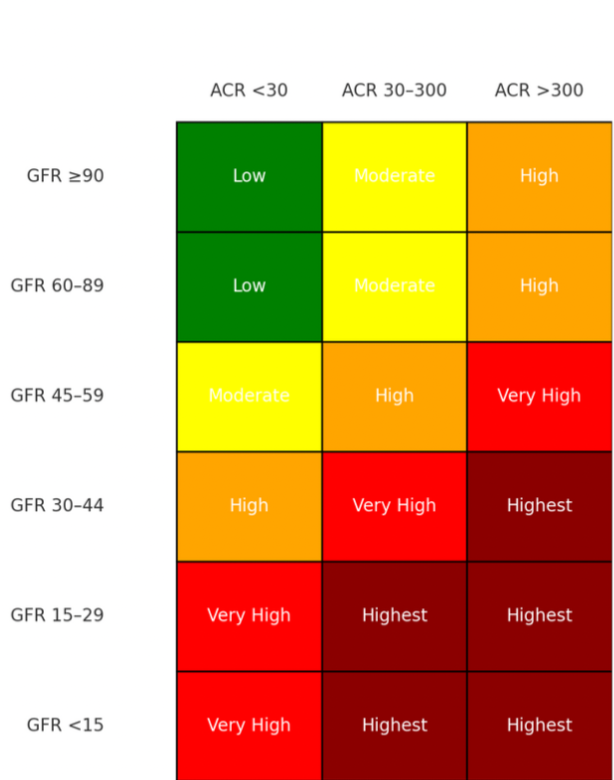

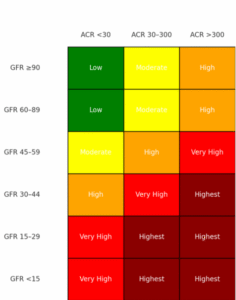

Under normal conditions, the glomerular barrier prevents significant protein leakage. But when this barrier becomes damaged—through diabetes, hypertension, or primary glomerular disease—albumin crosses into the urine. Persistent albuminuria not only reflects existing injury but also accelerates further decline, compounding the progression of CKD. GFR and stage of CKD plotted again the magnitude of proteinuria can give a better idea of progression risk on the CKD Heat Map at NKF.org heat_map_card.pdf.

In many cases, albuminuria develops gradually. But in glomerular diseases, it may appear suddenly and in large amounts. These require a kidney biopsy for diagnosis and include:

- Minimal Change Disease

- Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

- Membranous Nephropathy

- IgA Nephropathy

- Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis (MPGN)

These primary glomerulopathies are often immune-mediated, and in select cases, immunotherapy is required. Corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., tacrolimus), mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, and biologics like rituximab are used depending on the disease subtype, severity, and biopsy findings.

For example, membranous nephropathy—linked to anti-PLA2R antibodies—may respond to rituximab or cyclical steroid-based regimens. Steroid-resistant FSGS might call for calcineurin inhibitors. Rapidly progressive IgA nephropathy may warrant a pulse steroid protocol followed by immunosuppressive maintenance.

Initiating immunotherapy is not a blanket decision. It requires careful clinical judgment, balancing histologic activity, rate of GFR decline, volume of proteinuria, and overall patient risk. Nephrologists often rely on kidney biopsy and serologic markers to determine timing and intensity.

Even outside the setting of glomerulonephritis, reducing proteinuria is a central goal. KDIGO guidelines recommend classifying albuminuria into three risk categories (A1–A3), and pairing this with eGFR to estimate disease trajectory. The greater the albuminuria, the higher the chance of rapid progression of CKD—even if GFR is temporarily preserved.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are the primary pharmacologic tools to reduce albuminuria. These agents help lower glomerular pressure and restore barrier selectivity. SGLT2 inhibitors also reduce proteinuria, providing additive benefit when used in combination.

Lifestyle factors also matter. A low-sodium diet enhances the effect of RAAS blockade, and plant-forward eating may help reduce glomerular stress. Regular monitoring of urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) allows both patients and providers to track response and adjust therapy.

Ultimately, albuminuria offers a window into glomerular health—and an actionable target for intervention. Addressing it early and aggressively can significantly alter the progression of CKD, whether the root cause is metabolic, vascular, or immunologic.

Genetics and Family History

While many risk factors for CKD are related to lifestyle or comorbid conditions, some lie hidden in the genetic code. For a significant subset of patients, the progression of CKD is influenced—or even initiated—by inherited mutations that alter kidney development, structure, or function.

A family history of kidney disease, particularly when it spans multiple generations or presents early in life, often points to a heritable condition. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is the most well-known genetic cause, but it is not alone. Other monogenic disorders include Alport syndrome, Fabry disease, thin basement membrane disease, and various forms of autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD). While genetic variant markers of significance may not help delay progression of CKD, this knowledge can help with predicting prognosis and identifying other relatives who may be at risk for kidney impairment.

Until recently, confirming these conditions required referral to a specialty center. Today, however, clinical-grade genetic testing is widely available. Many nephrology clinics now offer in-house panel testing that screens for dozens of pathogenic variants using a simple blood or saliva sample. These tests are often covered by insurance and are increasingly recognized as standard of care in specific clinical scenarios.

According to KDIGO and recent expert consensus, genetic screening should be considered when:

- CKD has an unclear cause

- There’s a strong family history of kidney failure, especially under age 50

- Glomerular disease is suspected based on biopsy or urine findings

- Extrarenal signs (e.g., hearing loss, vision changes, vascular anomalies) are present

- The patient is a potential kidney donor with a biologic relative who has CKD

Identifying a genetic variant can profoundly shape care. For example, detecting a COL4A5 mutation in Alport syndrome informs not only kidney prognosis but also the need for audiologic and ophthalmologic surveillance. Knowing that a patient has ADPKD might prompt blood pressure adjustments, imaging for cerebral aneurysms, and counseling for family members.

These insights can also shift the trajectory of care. In some cases, specific therapies may be available. For instance, enzyme replacement for Fabry disease or clinical trials targeting PKD pathways may be appropriate. Even when no targeted treatment exists, surveillance protocols and lifestyle recommendations can be adjusted to mitigate risk.

Importantly, genetic findings have implications beyond the individual. Cascade testing of family members can reveal asymptomatic carriers, enabling earlier intervention and delaying the progression of CKD across generations.

Of course, not all genetic variants are clearly pathogenic. Many are labeled as “variants of uncertain significance” and require clinical correlation. This is where genetic counseling proves essential—to ensure results are interpreted in context and used to inform, not confuse, decision-making.

Genetics will never be the whole story, but for many patients, it’s an overlooked chapter. Acknowledging its role can unlock personalized strategies to understand, anticipate, and slow the progression of CKD in families as well as individuals.

Additional Contributors to CKD Progression

While hypertension, diabetes, proteinuria, and genetics receive deserved attention, the progression of CKD is rarely shaped by a single force. Instead, it reflects a complex interplay of factors—some obvious, others subtle—that cumulatively tip the balance toward decline.

One such factor is acute kidney injury (AKI). Many CKD patients experience AKI from dehydration, infections, medication exposure, or contrast dyes. Even when seemingly resolved, these events may leave residual damage that lowers baseline kidney function. Moreover, each episode increases the risk of future AKI, establishing a feedback loop that can quietly accelerate the progression of CKD.

Medications also play a significant role—sometimes helpfully, sometimes harmfully. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), certain antibiotics, and over-the-counter agents like high-dose vitamin C or some herbal remedies can cause direct nephrotoxicity or precipitate AKI. The margin for error narrows as kidney function declines, making careful medication review essential.

Obstructive uropathy is another contributor, particularly in older adults. Conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia, recurrent kidney stones, or neurogenic bladder may lead to backpressure, hydronephrosis, and secondary scarring. Often overlooked, these structural issues can be reversible if detected early. Simple tests like a post-void residual ultrasound or bladder scan can be used to rule out this problem and prevent long-term kidney damage.

Cardiovascular disease deserves special mention. Heart failure can reduce renal perfusion and create venous congestion—a dynamic known as cardiorenal syndrome. In this state, poor cardiac output compromises kidney filtration, while fluid overload increases intraglomerular pressure. Collaborative management between nephrology and cardiology is critical to slow the progression of CKD in this dual-threat context.

Other systemic contributors include:

- Obesity, which raises intraglomerular pressure and is associated with secondary FSGS

- Sleep apnea, which causes intermittent hypoxia and sympathetic activation

- Smoking, a direct vascular and inflammatory insult

- Chronic inflammation, often present in autoimmune disease or metabolic syndrome

Equally impactful, though less medical in appearance, is nonadherence. Even the most carefully prescribed regimen will fail if not followed. Barriers like medication cost, pill burden, depression, or low health literacy can derail otherwise effective care. Building trust, simplifying regimens, and engaging patients in shared decision-making are vital steps in preventing unnecessary decline.

Each of these elements, on its own, may only nudge kidney function downward. But together—layered over time—they shape the slope of the curve. Recognizing these influences allows clinicians and patients to intervene early, adjust plans, and reduce the burden that silently pushes the progression of CKD forward.

The Role of Medical Management and Lifestyle Choices

Slowing the progression of CKD requires more than identifying risk factors—it demands precise, individualized treatment. While patient characteristics vary, many components of care now fall under the umbrella of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), an evidence-based approach adapted from cardiology and increasingly central in nephrology.

At the heart of GDMT in CKD are several foundational therapies:

- RAAS Blockade (ACE inhibitors or ARBs): These medications lower both systemic and intraglomerular pressure, reducing proteinuria and preserving nephron integrity. They remain the cornerstone of treatment in proteinuric CKD, even when blood pressure is otherwise controlled.

- SGLT2 Inhibitors: These have transformed CKD management. By reducing sodium and glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule, they lower glomerular pressure and slow fibrosis. Landmark trials (DAPA-CKD, EMPA-KIDNEY) have shown a consistent ability to delay dialysis and reduce cardiovascular events—across diabetic and non-diabetic populations. They are now first-line agents for many with Stage 2–4 CKD.

- Nonsteroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (nsMRAs): Finerenone and similar agents target fibrotic and inflammatory pathways in the kidney, especially in diabetic patients with persistent proteinuria despite RAAS therapy. They provide additive benefit, though require careful potassium monitoring.

- GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: These are useful in patients with diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular risk. While their renal benefits are less direct, their weight loss and metabolic effects support long-term stability and complement other therapies aimed at the progression of CKD.

Importantly, GDMT is not a checklist. Not every patient tolerates every agent. Nephrologists must tailor regimens based on eGFR, potassium levels, blood pressure, comorbidities, and medication access. This personalized approach respects the reality of polypharmacy and patient preference, rather than enforcing rigid protocols.

Monitoring is key. Many of these agents require lab follow-up—especially to check electrolytes and assess for volume changes. Adjustments are often needed as kidney function shifts. But with careful oversight, these therapies can be used safely and synergistically.

Medical therapy, however, is only half the equation. Lifestyle choices remain powerful modulators of risk:

- Sodium restriction enhances medication efficacy and reduces blood pressure

- Plant-predominant diets (like CKD-modified DASH or Mediterranean) reduce glomerular load and inflammation

- Exercise, even in modest amounts, improves vascular health and insulin sensitivity

- Smoking cessation, adequate sleep, and stress management round out a holistic kidney strategy

Shared decision-making empowers patients to participate fully in shaping their care. When the treatment plan aligns with the patient’s goals, beliefs, and routines, adherence improves—and so do outcomes.

The progression of CKD is not a fate sealed at diagnosis. With modern therapy and consistent lifestyle habits, patients can chart a course that preserves function, prolongs independence, and improves quality of life.

Takeaway: What You Can Do to Slow CKD Progression

Chronic kidney disease may be silent in its early stages, but it speaks volumes through trends—blood pressure patterns, lab shifts, urinary markers, and more. When patients and clinicians tune in together, they can change the narrative. The progression of CKD is real—but it’s not inevitable.

The first step is recognizing the landscape. The primary risk factors—hypertension, diabetes, proteinuria, and genetic predisposition—account for much of the burden. But other contributors like recurrent AKI, harmful medications, obesity, sleep apnea, and even stress can all influence how quickly or slowly CKD advances.

Next comes monitoring. Routine labs—serum creatinine, eGFR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, potassium—offer a window into kidney health. When tracked over time, these values reveal trends that can inform timely intervention. An uptick in albuminuria? It may be time to intensify therapy. A drop in eGFR? Consider medication review or imaging. These patterns guide decisions that can blunt or even reverse the progression of CKD.

Then comes action. Medical therapy today is far more advanced than it was a decade ago. Patients have access to:

- RAAS blockers to reduce glomerular stress

- SGLT2 inhibitors to slow fibrosis and improve cardiovascular outcomes

- Finerenone and GLP-1 agonists to reduce inflammation and metabolic strain

But medications work best in the context of consistency. Taking them as prescribed, following up on labs, and discussing side effects early can preserve their benefit and limit risk. This is where communication with your nephrologist becomes central. Bring questions. Bring your home blood pressure log. Bring your goals.

Lifestyle is equally influential. Reducing sodium, following a plant-forward diet, moving daily, and getting adequate sleep all help protect kidney function. Small changes can make a meaningful difference. Even stress management—through mindfulness, hobbies, or counseling—can reduce hormonal drivers of progression.

Perhaps most important is staying engaged. CKD doesn’t always feel like an emergency, but waiting for symptoms to emerge usually means you’re late to the game. Early action is quieter but more powerful. Catching trends, modifying risks, and aligning treatments before severe decline occurs is the true path to preserving kidney health. Remember, a boring kidney appointment is usually a good kidney appointment – but remain motivated and vigilant especially when things are going well.

The progression of CKD may be common, but it is not unchangeable. For many, it can be slowed. For some, it can be stopped. And in all cases, there is value in taking deliberate, informed steps forward.

You are not powerless in the face of kidney disease. With vigilance, partnership, and the tools of modern medicine, you can influence your outcome—and extend the health of your kidneys for years to come.

References

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2021;99(3S):S1–S87. https://kdigo.org/guidelines/blood-pressure-in-ckd/

- de Boer IH, Caramori ML, Chan JCN, et al. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2022;102(5S):S1–S127. https://kdigo.org/guidelines/diabetes-ckd/

- Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1436–46. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2024816

- Savige J, Ariani F, Knollmeyer J, et al. Expert consensus guidelines for the genetic diagnosis of Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(7):1175–89. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00467-019-04174-7

- Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2219–29. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2025845