Proteinuria: Cause for Concern, Target for Treatment, and Prognostic Indicator

What is proteinuria?

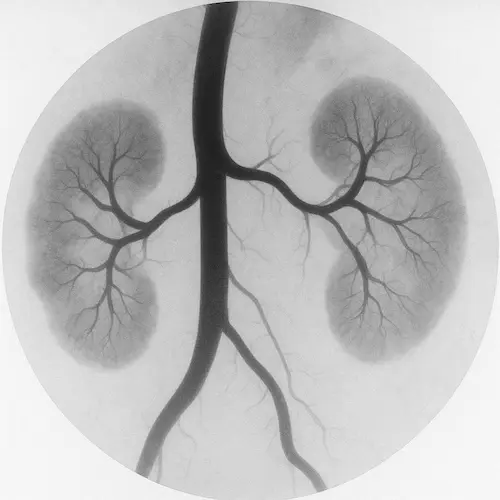

Proteinuria means there is an abnormal amount of protein in the urine. Normally, your kidneys act as a filter to keep important substances like protein in your blood, while removing waste through urine. When the filtering units (called glomeruli) become damaged or inflamed, protein can leak into the urine.

There are small amounts of protein in everyone’s urine occasionally—especially after heavy exercise or illness. But persistent or high levels may indicate a problem with kidney function. Proteinuria is often one of the earliest signs of kidney damage, especially in people with diabetes or high blood pressure.

Why is protein in the urine a concern?

Protein is essential for building and repairing body tissues, regulating fluid balance, and supporting immune function. When it’s lost in the urine, it’s not just a marker of kidney stress—it’s a sign that the filtration system itself is compromised.

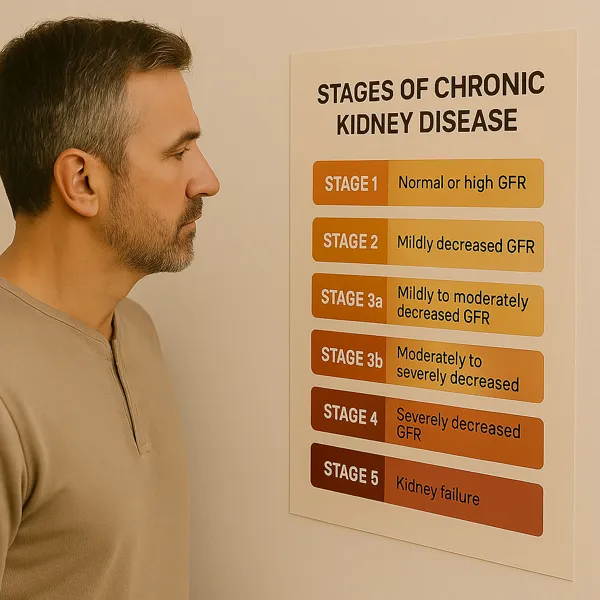

Over time, ongoing proteinuria can cause inflammation and scarring in the kidney tubules, which accelerates the loss of kidney function. The more protein you lose, the faster your risk of progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD) or even kidney failure.

Additionally, protein loss is linked to other complications such as:

- Swelling (especially in the legs or face)

- Higher risk of cardiovascular disease

- Lower blood protein levels (e.g., albumin)

- Elevated cholesterol or triglycerides

What causes proteinuria?

There are many possible causes, ranging from temporary conditions to chronic disease. Some of the most common include:

- Diabetic kidney disease (diabetic nephropathy)

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Glomerular diseases, such as:

- Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

- IgA nephropathy

- Membranous nephropathy

- Infections (e.g., urinary tract or kidney infections)

- Pregnancy-related conditions like preeclampsia

- Heavy exercise or fever (transient proteinuria)

- Orthostatic proteinuria, which occurs when standing for long periods and resolves at rest (typically in younger people)

In rarer cases, proteinuria may be due to certain cancers, autoimmune conditions (like lupus), or genetic kidney disorders.

How is proteinuria detected?

Proteinuria is usually discovered through a routine urinalysis. There are two main tests:

- Dipstick urine test – A quick screening that detects the presence of protein but not the exact amount.

- Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) or albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) – These provide a more precise, standardized measure of protein levels. They can be done on a single urine sample and help determine the severity.

Your doctor may order repeat tests to confirm the finding, rule out transient causes, and track changes over time.

When should proteinuria be monitored—and when should it be treated?

This depends on the amount of protein, how long it has been present, and whether there are other signs of kidney dysfunction. Here’s a general guide:

| Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio (UACR) | Interpretation | Action |

|---|---|---|

| < 30 mg/g | Normal to mildly increased | Monitor annually if at risk |

| 30–300 mg/g | Moderately increased (microalbuminuria) | Monitor every 3–6 months; assess cause |

| > 300 mg/g | Severely increased | Actively treat and investigate cause |

If proteinuria is accompanied by decreased GFR, elevated blood pressure, or abnormalities in bloodwork, more urgent evaluation is warranted. Patients with high-level protein loss may need a referral to a nephrologist and possibly a kidney biopsy to determine the exact cause.

How is proteinuria treated?

Treatment depends on the underlying condition. Some general principles include:

- Blood pressure control: Especially with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, which reduce intraglomerular pressure and protein loss.

- Glycemic control: Tight control of blood sugar in diabetes reduces the progression of proteinuria.

- SGLT2 inhibitors: These medications, used in both diabetic and non-diabetic CKD, have been shown to reduce proteinuria and slow kidney disease progression.

- Dietary sodium restriction: Enhances medication effect and reduces fluid retention.

- Immunosuppressive therapy: In glomerular diseases, medications like corticosteroids or rituximab may be used to treat inflammation.

- Cholesterol management: Statins are often prescribed, as proteinuria is associated with dyslipidemia.

Lifestyle changes—including exercise, avoiding NSAIDs, stopping smoking, and limiting processed foods—support medical management and reduce cardiovascular risk.

When is a kidney biopsy necessary?

A kidney biopsy may be recommended when:

- Proteinuria is severe or increasing rapidly

- Kidney function is declining without a clear explanation

- Other lab tests or imaging suggest glomerular disease

- The patient is young or has a family history of kidney conditions

The biopsy helps identify the exact diagnosis, which guides therapy. In some cases, identifying a specific glomerular disease may open the door to immunotherapy or targeted treatment.

What can I do if I have proteinuria?

If you’ve been told you have proteinuria, here are steps you can take immediately:

- Follow up with repeat testing to confirm and quantify the protein level

- Work with your doctor to identify the cause—this may include checking kidney function (eGFR), blood pressure, diabetes status, and reviewing medications

- Make lifestyle changes that support kidney health: reduce salt, quit smoking, maintain a healthy weight

- Take prescribed medications consistently, especially those that reduce protein leakage (like ACE inhibitors or SGLT2 inhibitors)

- Ask about nephrology referral if your protein levels are high or rising

Early recognition and treatment can slow or stop the proteinuria from leading to long-term kidney damage.

Does proteinuria always mean kidney failure?

No. Many cases of proteinuria are mild and reversible—especially when caught early. Some forms may persist without progressing to serious kidney damage. But persistent, moderate-to-high levels of protein in the urine are a strong warning sign and should never be ignored.

Monitoring, understanding your numbers, and acting early are the keys to protecting your kidneys and overall health.

References

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(2):139–274.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care.

- Heerspink HJL, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. NEJM. 2020.

- National Kidney Foundation. “Protein in Urine (Proteinuria).”