Diabetic Kidney Disease – Where Lifestyle and Medical Management are Essential for Optimizing Care

If diabetes is the storm, the kidneys are often its silent shoreline—weathered over time until the signs of damage become hard to ignore. Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide, affecting nearly 1 in 3 adults with diabetes. But for many, the diagnosis arrives without thunder—just a note in the portal, a flagged lab, or an offhand remark about “protein in the urine.”

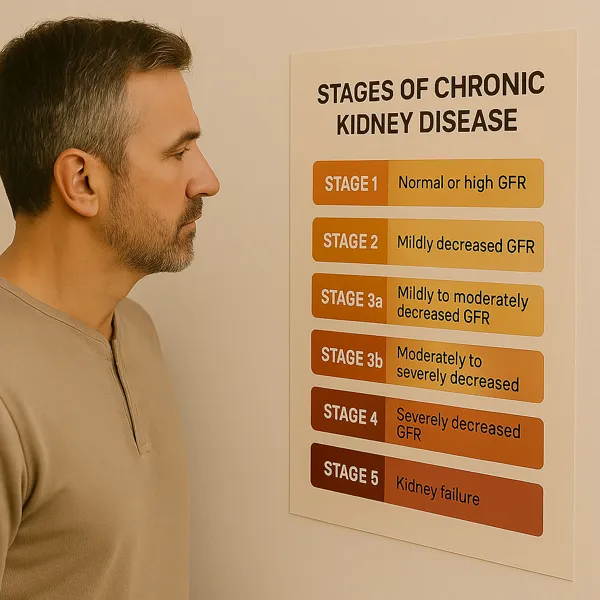

DKD doesn’t announce itself with pain. It progresses quietly—through elevations in albuminuria, dips in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and the insidious erosion of reserve. For years, it was assumed that once kidney damage set in, decline was inevitable. But that mindset is no longer acceptable.

We now know that timely intervention—through both lifestyle changes and goal-directed medical therapy—can dramatically slow progression, reduce complications, and extend years of independence before dialysis or transplant ever enter the picture.

This post explores the essentials of DKD care: what it is, how it behaves, and what patients and clinicians can do—together—to protect kidney function while honoring the complexity of diabetes as a systemic disease. We’ll unpack the labwork, the medications, the nutrition, and the turning points that guide whether we intervene gently, intensively, or prepare for transitions of care.

Because managing diabetic kidney disease isn’t about choosing between diet or drugs—it’s about understanding that both are vital. And when combined with patient engagement and consistent monitoring, they offer more than just delay—they offer dignity and control.

What is Diabetic Kidney Disease?

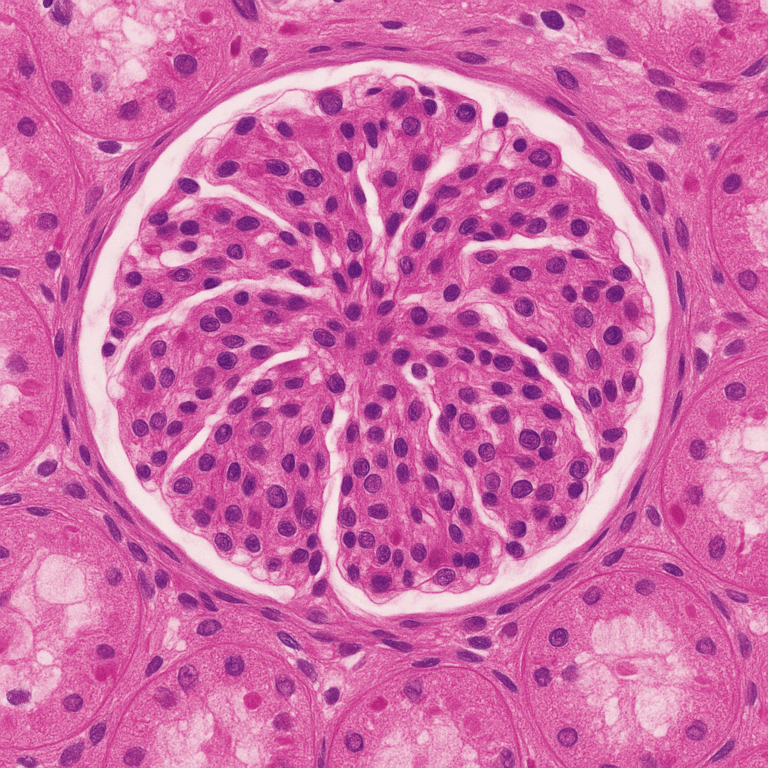

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) refers to progressive kidney damage resulting from the long-term effects of diabetes mellitus, particularly Type 2 diabetes. It’s a clinical condition defined not just by declining filtration function but by a pattern of injury that reflects years of elevated glucose, hemodynamic stress, and microvascular insult to the kidney’s filtration system.

Unlike some kidney disorders that arise abruptly, DKD usually unfolds gradually:

- Initially, there may be microalbuminuria—small amounts of protein leaking into the urine.

- Over time, this can evolve into macroalbuminuria and measurable declines in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

- Eventually, the kidneys may lose their ability to maintain electrolyte balance, fluid status, and toxin clearance.

But DKD is more than just a kidney problem. It is a marker of widespread vascular dysfunction. The presence of protein in the urine in a diabetic patient significantly raises the risk of heart attack, stroke, and premature mortality. In fact, in many cases, cardiovascular events, not kidney failure, are the first major complication to emerge.

Common Clinical Features of DKD:

- Persistent albuminuria (≥30 mg/g) confirmed on repeat testing

- Declining eGFR, often over months to years

- Hypertension that becomes more difficult to control

- Edema or swelling, especially in the lower extremities

- Anemia or rising potassium in later stages

Importantly, DKD can exist even when blood sugar appears “under control.” The damage may have been set in motion years earlier. That’s why early screening and proactive management are essential, even in patients without symptoms.

Blood Sugar Control is Important, But Not Enough.

For decades, the cornerstone message to patients with diabetes has been: control your blood sugar to protect your kidneys. While that advice remains foundational, it’s no longer the full story. In diabetic kidney disease, glucose is only one part of a complex network of damaging forces—many of which unfold independently of A1C.

So why isn’t tight glucose control enough?

Because DKD is multifactorial. It involves:

- Hemodynamic stress: High blood pressure causes direct injury to glomerular capillaries, worsening protein leakage and accelerating scarring.

- Metabolic toxicity: Lipid abnormalities, insulin resistance, and glycation end products contribute to inflammation and fibrosis.

- Neurohormonal activation: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), sympathetic nervous system, and other pathways promote vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and hypertrophy.

- Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction: These impair the fine-tuned regulation of kidney perfusion and repair.

This means that even a patient with an A1C of 6.9% can have progressive DKD if other drivers—like hypertension or albuminuria—go unchecked.

Clinical Evidence Confirms This:

Landmark studies like ADVANCE, UKPDS, and ACCORD have shown that while tight glucose control reduces microvascular complications, it does not eliminate DKD risk, and aggressive glucose lowering can even cause harm in some populations, particularly the elderly.

That’s why modern DKD management focuses on multi-pronged control:

- Glycemic management (with kidney-safe agents)

- Blood pressure optimization

- Reduction of albuminuria

- Cardiovascular risk modification

- Lifestyle intervention

Blood sugar is just the beginning—not the finish line.

The Role of Lifestyle Modification in Slowing DKD Progression.

If medications are the framework of diabetic kidney disease management, then lifestyle is the foundation—and without it, the structure falters. No therapy can fully substitute for the power of nutrition, physical activity, and informed habits. These choices influence not only blood sugar and blood pressure, but also the systemic inflammation, endothelial health, and metabolic stability that shape the trajectory of kidney disease.

Key Lifestyle Strategies for DKD:

Nutrition: Less Salt, Better Protein, Smarter Carbs

- Sodium: Excess salt increases blood pressure and worsens proteinuria. Aim for <2,300 mg/day—or lower if advised.

- Protein: Contrary to myth, most patients don’t need to over-restrict protein, but excessive intake (e.g., keto diets) may accelerate decline. Moderate, high-quality sources are best.

- Carbohydrates: Prefer low glycemic index foods (e.g., lentils, whole oats, berries) over refined carbs. This smooths post-meal glucose spikes and supports overall metabolic balance.

Physical Activity

- Even 20–30 minutes of walking most days can improve insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and cardiovascular health.

- Avoiding a sedentary lifestyle is more important than achieving elite fitness.

Tobacco Cessation

- Smoking is a direct toxin to the kidneys, worsening vascular injury and accelerating CKD.

- Cessation programs can double quit success rates and improve long-term outcomes.

Weight Management

- Modest weight loss (5–10%) can improve glycemic control and blood pressure.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors (when appropriate) may assist this process alongside diet and exercise.

What Diet Is Best for Diabetic Kidney Disease?

Q: Should I follow a kidney diet or a diabetes diet?

A: Both—and neither. The ideal diet for DKD blends the best features of each: low sodium, heart-healthy fats, controlled carbohydrates, and a reasonable protein intake based on your stage of CKD. This often looks like a Mediterranean-style or plant-forward approach adjusted for potassium and phosphorus if needed.

Medications that Protect the Diabetic Kidney

In the past, diabetic kidney disease was managed largely through glucose control and blood pressure targets. Today, goal-directed medical therapy (GDMT) has transformed the treatment landscape—shifting from passive observation to active risk modification with medications that offer direct kidney protection, not just glucose lowering.

But here’s the nuance: these therapies must be selected and tailored by a nephrologist or CKD-knowledgeable clinician, because DKD is not a one-size-fits-all diagnosis.

Medication Classes That Matter in DKD

1. RAAS Inhibitors – ACE Inhibitors and ARBs

- Reduce intraglomerular pressure and proteinuria

- Lower cardiovascular and renal risk

- First-line in patients with albuminuria >30 mg/g, even without hypertension

- Monitoring: potassium, creatinine after initiation or dose change

2. SGLT2 Inhibitors – Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Blockers

- Reduce progression of CKD independent of A1C

- Lower risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death

- Agents like dapagliflozin and empagliflozin are now approved specifically for CKD and heart failure patients

- May cause modest volume loss—monitor hydration status

3. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists – Glucose-Lowering and Weight-Reducing

- Promote weight loss, improve A1C

- Cardioprotective in multiple trials

- May have anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects on the kidney (investigational)

- Injectable formulations, with GI side effects as common limitation

4. Finerenone – Non-Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist

- Reduces albuminuria and CKD progression

- Shown to lower CV events in patients with DKD (FIDELIO-DKD trial)

- Requires potassium monitoring, especially when combined with RAAS blockers

Why GDMT Isn’t a Checklist

Not all patients can tolerate every agent. Side effects, comorbidities, cost, GFR thresholds, and individual goals all influence therapy choices. That’s why collaboration with a nephrologist is crucial: we’re not just picking from a menu—we’re crafting a personalized, dynamic plan that balances protection with tolerability.

Signs of Progression and Considerations in ESKD

Despite the best efforts of patients and providers, some individuals with diabetic kidney disease will experience ongoing progression. Recognizing early signs of decline and adjusting care accordingly is a vital part of kidney protection—especially as patients approach end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).

Signs That DKD May Be Progressing:

- Falling eGFR, especially if decline is sustained across multiple labs

- Worsening albuminuria, despite stable blood sugar and blood pressure

- Uncontrolled hypertension, even with three or more medications

- Metabolic acidosis (low bicarbonate levels)

- Rising phosphorus or falling calcium, suggesting impaired mineral balance

- Persistent anemia unresponsive to iron or diet alone

- New or worsening edema, fatigue, or shortness of breath

Progression doesn’t always follow a straight line—but trends matter. A drop of more than 5 mL/min/1.73 m² per year may warrant closer follow-up and referral to nephrology if not already under specialist care.

Medication Adjustments in Advanced DKD

As GFR falls, certain diabetic medications become risky or ineffective and may need to be reduced or stopped.

Medications to Use With Caution or Avoid:

- Metformin: Risk of lactic acidosis rises when GFR drops below 30. Titrate down or discontinue based on thresholds.

- Long-acting sulfonylureas (e.g., glyburide): Increased risk of prolonged hypoglycemia due to reduced renal clearance.

- NSAIDs: Can worsen intraglomerular perfusion and precipitate AKI in CKD.

A Hidden Signal: Decreasing Insulin Needs

The kidneys help break down insulin, so as kidney function declines, insulin sticks around longer in the bloodstream. If a person with longstanding diabetes suddenly needs less insulin to maintain the same blood sugar levels, it could be a red flag of declining GFR.

This phenomenon, while seemingly positive at first glance, may actually reflect accumulating toxins and altered metabolism—requiring further evaluation.

Planning Ahead for ESKD

If GFR approaches <20 mL/min/1.73 m², patients should begin learning about:

- Dialysis options (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis)

- Pre-emptive kidney transplantation

- Conservative management, if appropriate for personal goals

Early planning avoids emergency starts and helps patients retain control and dignity in the face of difficult decisions.

Patient Empowerment – You are Your Own Best Advocate.

Diabetic kidney disease may sound clinical—but for patients, it’s deeply personal. The journey isn’t just about numbers—it’s about regaining agency in a system that can feel overwhelming. The good news? With the right tools and a proactive mindset, patients can be more than passengers—they can drive their care forward.

Own Your Numbers, But Don’t Be Owned by Them

- Know your eGFR and UACR—ask for trends, not just snapshots.

- Monitor your blood pressure at home.

- Track symptoms: fatigue, swelling, shortness of breath, appetite, or sleep patterns.

Knowledge empowers—but obsessing over a single reading can cause unnecessary fear. Focus on patterns, and share concerns with your team.

Build a Relationship With Your Kidney Team

- A nephrologist is your kidney specialist—early referrals (often when eGFR drops <45 or UACR is elevated) can preserve function longer.

- Endocrinologists, primary care providers, dietitians, and pharmacists all contribute to comprehensive care.

- Don’t hesitate to ask: “What are we doing to protect my kidneys?”

Use the Tools Available to You

- Mobile apps to track labs, meds, and diet

- Educational resources like the National Kidney Foundation

- Support groups—virtual or local—especially helpful in navigating lifestyle changes

Remember: Decline Isn’t Destiny

Many patients live years or decades with stable kidney function. Even when eGFR falls, slowing the slope matters. Every year of preserved function is a year with fewer symptoms, fewer interventions, and greater freedom.

When lifestyle and medical therapy walk side by side, and when patients are supported—not overwhelmed—DKD becomes not just manageable, but navigable.

Works Cited

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in CKD. Kidney Int. 2022;101(4S):S1–S127.

- American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024 Jan;47(Suppl 1):S199–S219.

- National Kidnehttps://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/diabetesy Foundation: Diabetes and Kidney Disease.