Genetic Disorders in CKD: Spotlight on Polycystic Kidney Disease

What Is Polycystic Kidney Disease?

Imagine standing on a shoreline where the tide creeps in millimeter by millimeter—so slowly that you barely notice until the water surrounds your ankles. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) moves with similar stealth. At birth the kidneys may look ordinary, yet microscopic cysts—tiny balloons of fluid—lie waiting. Over decades they multiply, swell, and displace healthy filtering tissue. By the time many people feel flank discomfort or see blood in the urine, significant damage is already done.

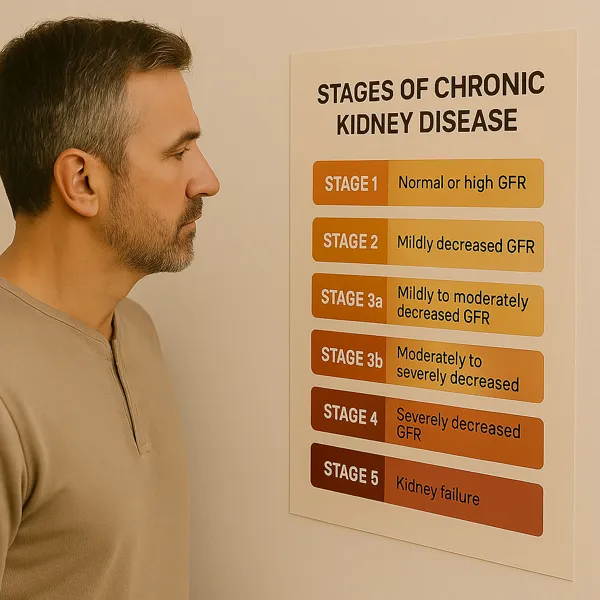

Unlike most causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD), polycystic kidney disease is almost always genetic. Mutations in PKD1 or PKD2 genes disrupt the tubule‑lining cells’ calcium signaling, triggering uncontrolled cell division and cyst formation. The kidneys, normally the size of a fist, can enlarge to the size of a football, weighing up to 15 lb each. This silent growth sets PKD apart—many patients appear perfectly healthy until routine labs reveal falling estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Genetic Paths: ADPKD vs ARPKD

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

ADPKD accounts for about 1 in every 500–1 000 births, making it one of the most common inherited disorders worldwide. A single faulty gene from one parent confers a 50 % transmission risk in each pregnancy. PKD1 mutations generally produce earlier, faster decline than PKD2, though individual trajectories vary.

Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD)

ARPKD strikes roughly 1 in 20 000 births and requires both parents to carry a pathogenic variant of the PKHD1 gene. Infants may present with massively enlarged kidneys, breathing difficulties from compressed lungs, and liver involvement that persists lifelong. Advances in neonatal intensive care have improved survival, yet these children still face complex, multidisciplinary management.

Genetic testing, once niche and costly, is now widely available. A cheek swab can confirm diagnosis, stratify risk, and guide family planning. Even adults with no known family history should consider testing if imaging suggests cystic disease—up to 10 % of ADPKD cases arise from spontaneous mutations.

Early Signs, Diagnosis, and Monitoring

High blood pressure is often the first clinical clue. Cysts activate the renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system, driving hypertension years before eGFR slips. Recurrent kidney stones, urinary tract infections, and dull flank heaviness follow.

Ultrasound remains the frontline test: three or more bilateral cysts in a 15‑ to 39‑year‑old with an affected parent confirm ADPKD. For equivocal cases, MRI quantifies total kidney volume (TKV)—a powerful predictor of future decline. Annual TKV growth > 5 % flags a “rapid progressor” who may benefit from disease‑modifying therapy. See more in our imaging rundown entry.

Labs every 6–12 months track serum creatinine, electrolytes, and liver enzymes if on tolvaptan. Early referral to nephrology ensures timely education, complication screening, and transplant evaluation when the moment arrives.

Complications and Progression Risks

Unchecked hypertension accelerates cyst expansion, proteinuria, and scarring, making polycystic kidney disease march faster toward kidney failure. Beyond the kidneys, liver cysts can cause fullness and early satiety; weak spots in cerebral arteries may balloon into aneurysms; and mitral‑valve prolapse can trigger palpitations.

Pain—ranging from nagging ache to sudden, knife‑sharp bursts—often stems from cyst rupture or bleeding. Gross hematuria alarms patients yet usually resolves with rest and hydration. Recurrent bleeding, however, warrants imaging to rule out stones or infection.

By age 70, roughly 70 % of individuals with ADPKD will require dialysis or transplant. The trajectory isn’t uniform: TKV, genetic mutation type, blood‑pressure control, and lifestyle choices influence the slope. That variability underscores why individualized monitoring is vital. Realize these statistics do not take into account the benefits of modern drug therapy. In general, every four years on tolvaptan can delay onset of dialysis an extra year or longer.

Other organ involvement is variable in Polycystic Kidney Disease. Cysts can also develop in the liver and less frequently in the pancreas. This is also an increased incidence of diverticulosis in the colon and brain aneurysms. In fact, if there is family history of aneurysm or stroke in a PKD family line, this can be an indication for obtaining an MRA of the brain to screen for Berry aneurysms.

Aspiration of large kidney cysts is usually not pursued in Polycystic Kidney Disease due to risk of bleeding complications as well as lack of efficacy since the fluid tends to rapidly reaccumulate after drainage. Liver cysts, however, can sometimes be reduced in size with a procedure called “unroofing” by a specialized surgeon. More recently, less invasive techniques for unroofing have been developed by interventional radiologists but this is not yet widely available.

Lifestyle & Medical Management

Blood‑pressure mastery is cornerstone therapy. Targeting ≤ 110/75 mm Hg (when tolerated) with an ACE inhibitor or ARB slows TKV climb and preserves nephrons. Beyond pills, low‑sodium eating (< 2 g/day) tempers fluid retention and pressure spikes.

Learn more about managing blood pressure in CKD and why early control matters.

Hydration suppresses vasopressin, a hormone that fuels cyst growth. Adults without fluid restrictions should aim for ≥ 3 L water daily, spaced to avoid overnight trips disrupting sleep. Incorporating strength and aerobic training boosts cardiovascular resilience, though contact sports that risk cyst rupture (e.g., rugby, equestrian) may warrant caution.

NSAIDs can silently dent kidney perfusion; in general, this class of drug should be avoided in CKD. When imaging requires iodinated contrast, coordinate with your nephrologist for pre‑ and post‑procedure hydration recommendations.

Treatment Options and Emerging Research

Tolvaptan

The first FDA‑approved disease‑modifying drug for polycystic kidney disease is tolvaptan, a selective vasopressin V2‑receptor blocker. By lowering cAMP signaling inside cyst‑lining cells, it slows kidney enlargement and eGFR decline by ~30 %. Side effects include intense thirst, polyuria (often > 5 L/day), and idiosyncratic liver injury, necessitating monthly LFTs for 18 months then quarterly. Patients of childbearing potential need reliable contraception; pregnancy data remain limited.

This medication drives urine output so both volume and frequency of urination will increase as an expected result of taking this medication. This in turn drives thirst and typical fluid intake needs can exceed 4L daily. The medication is staggered so the morning dose is higher than the afternoon dose to allow for the majority of urine output to occur during the day. However, most patients on this medication will also have to get up at night to urinate.

Your doctor can check a urine study called the osmolality test to guide dosing for this medication. The goal is to have a low osmolality to show that the medication is adequately promoting a dilute urine.

Candidacy for this medication is in part determined by the size of the kidneys on imaging by calculating the Total Kidney Volume (TKV). This is also something that can be followed over time to assess response to treatment with goal of slowing the rate of expansion in kidney size. A specialized calculator for Polycystic Kidney Disease classification has been developed by Mayo Clinic to help guide tolvaptan candidacy.

Somatostatin Analogs

Octreotide and lanreotide show promise in reducing liver cyst volume, though kidney benefits are less robust. Trials are ongoing to define optimal dosing and quality‑of‑life impact.

Beyond the Horizon

- CFTR modulators aim to alter chloride transport and fluid secretion.

- Metformin is under study for AMPK activation and downstream cAMP reduction.

- CRISPR‑based editing tantalizes with curative potential, yet ethical and technical hurdles remain with respect to gene modification.

When eGFR dips below 20 mL/min/1.73 m², pre‑emptive transplantation offers superior survival and quality of life over dialysis. Still, many patients bridge with in‑center or home modalities; see our breakdown of dialysis options for practical comparisons.

Informed Consent & Shared Decision‑Making

Every choice—drug therapy, imaging frequency, surgical cyst drainage—carries trade‑offs. Nephrologists must discuss:

| Decision Point | Key Risks | Key Benefits | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tolvaptan start | Liver injury, polyuria, cost | Slower TKV growth | Intensive lifestyle + watchful waiting |

| Screening MRI for aneurysm | Contrast risk, anxiety | Early aneurysm repair saves lives | Clinical watch if low‑risk phenotype |

| Early transplant listing | Surgical risks, immunosuppression | Avoids dialysis burden | Home hemodialysis bridge |

Transparent dialogue respects autonomy, addresses fears, and promotes adherence—cornerstones of ethical care.

Living Well with PKD: Empowerment Strategies

Stability of renal function over time is now a realistic goal for patients with polycystic kidney disease. By tracking daily water intake, tracking home BP, avoiding caffeine, and choosing plant‑centric meals, she has kept eGFR stable for eight years. Her story echoes across support forums: knowledge transforms fear into agency.

Practical tips:

- Set phone reminders to sip water hourly.

- Share your genetic status with first‑degree relatives so they can screen early.

- Use PKD Foundation webinars for community and cutting‑edge updates.

- Schedule annual transplant‑center visits once eGFR < 30 to streamline future listing.

Living well with polycystic kidney disease is not merely survival—it can be a purposeful, vibrant path when guided by informed choices.

Key Takeaways

- Polycystic kidney disease is common, genetic, and often silent until significant damage occurs.

- Total kidney volume and blood‑pressure trends forecast progression; monitor both.

- Tolvaptan offers the first disease‑modifying option, but lifestyle pillars remain indispensable.

- Shared decision‑making ensures treatments align with patient values and evidence.

- Empowerment through education and community fosters resilience and hope.

Works Cited

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline on the Management of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. 2023. Available at: https://kdigo.org (accessed July 20 2025).

- Torres VE et al. Tolvaptan in Later‑Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383: 201–212.

- National Kidney Foundation. “Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease.” https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/ARPKD (accessed July 20 2025).